Marcos Jr.’s economic performance in his first 2 years

June 30 marked end of the second year of President Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr.’s administration. How did the Philippine economy perform, and are Filipinos better or worse off after two years?

The baseline year is 2021 and although Mr. Marcos came into office only in the second half of 2022, the performance for the whole year can be considered as an achievement or non-achievement of the new administration. This is because business and political stability was settled after the May elections, so there are seven months that can be credited to the incoming administration.

To add more context to the economic assessment, neighboring countries in the ASEAN are included to provide a regional comparison, and the large Asian economies are also included as proxies for the global economy. After all, China, India, and Japan are among the four largest economies in the world.

A total of 11 Asian economies are covered in this assessment. The country comparisons over nearly two years show the following trends.

1. When it comes to GDP performance, the Philippines was among the fastest growing countries in Asia — and the whole world actually — in 2022, 2023, and up to the first quarter (Q1) of 2024. Our neighbors Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia, and also India performed well.

2. The Philippines was able to consistently bring the unemployment rate down, from 7.8% in 2021 (baseline) to only 3.9% in Q1 2024. We had the highest unemployment rate of nearly 8% in 2021, thanks to the economic damage caused by the lockdown dictatorship in 2020-2021 (see Table 1).

Budget Secretary Amenah F. Pangandaman, as member of the economic team, expressed her continued optimism in the country’s growth prospects. She said that “our medium-term economic plan, our public spending focused on hard infrastructure and social services like education, our budget innovation via digitalization, and our open government transparency including procurement reforms are bearing fruit in terms of strengthening investor and business confidence in the country, which creates more jobs for our people.”

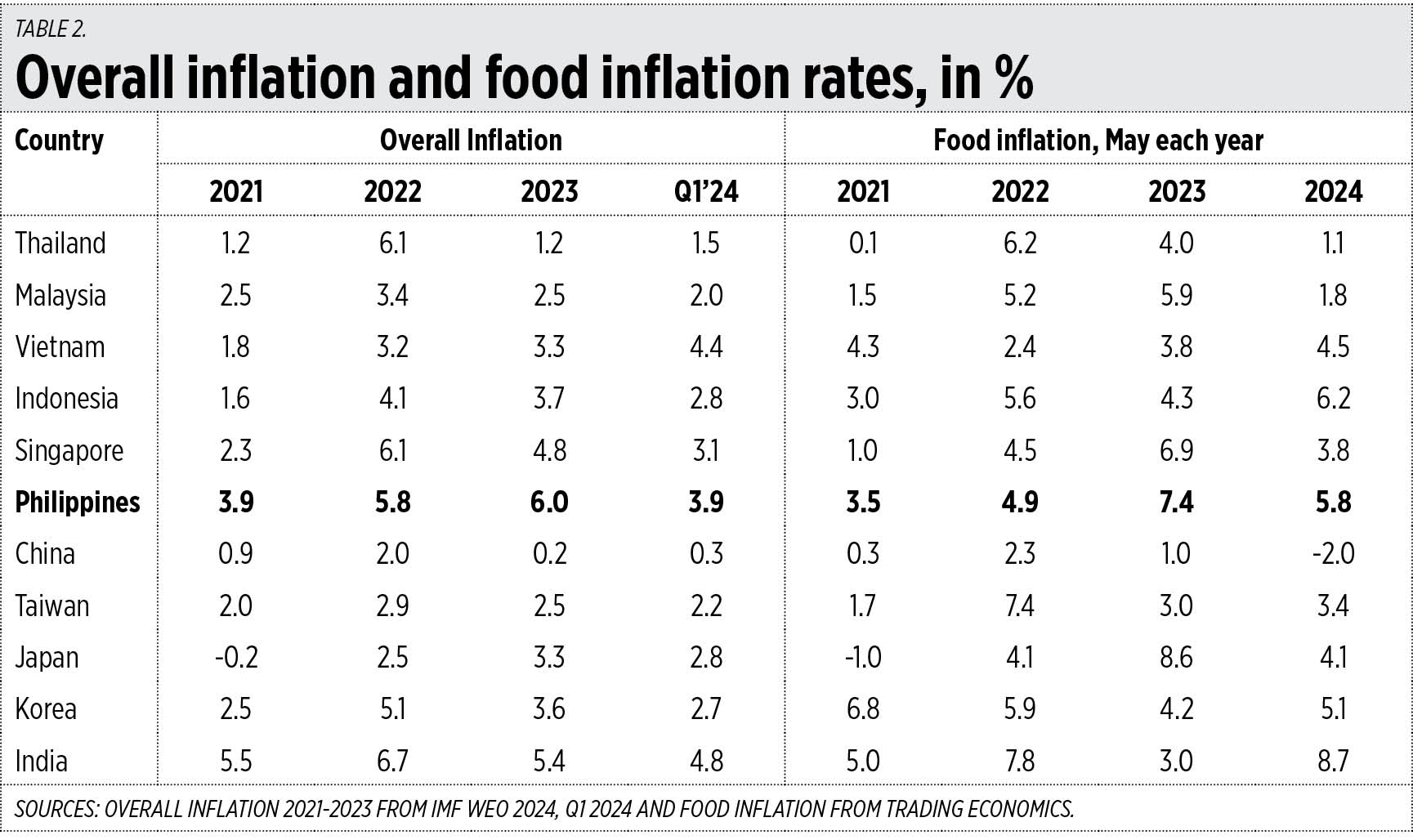

3. When it comes to price stabilization, the Philippines had the fourth highest inflation rate in 2022 and the highest in 2023 of the 11 economies considered. But by Q1 this year, it is back to 2021’s level of 3.9%. There is no full year average for food inflation in particular, so I picked food inflation in the month of May for each of the four years. The Philippines had the second highest food inflation in 2023 and the third highest in 2024 (see Table 2).

So, looking at these three important metrics — GDP growth, the unemployment rate, and the inflation rate — one sees that the Marcos Jr. administration did well in the first two but poorly in the third. One may argue that higher income growth and higher employment will allow the people to somehow deal with higher prices. But it is possible to have higher income and higher employment with lower inflation so we should pursue this path.

So, looking at these three important metrics — GDP growth, the unemployment rate, and the inflation rate — one sees that the Marcos Jr. administration did well in the first two but poorly in the third. One may argue that higher income growth and higher employment will allow the people to somehow deal with higher prices. But it is possible to have higher income and higher employment with lower inflation so we should pursue this path.

For the ASEAN-5 (the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia) in particular, I reviewed their overall inflation (OI) and food inflation (FI) monthly data over the past five years, from May 2019 to May 2024. Here is what I discovered:

The Philippines’ and Thailand’s FI are about 2% higher than their OI. Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s FI are about 2.5% higher than their OI. And Vietnam’s FI is only about 1.5% higher than its OI. So, among the ASEAN-5, Vietnam is in the best situation — having little difference between OI and FI.

I see that Vietnam has four policies that are more conducive to agriculture modernization than the Philippines.

One, they have no more forced land redistribution via endless, no time-table agrarian reform.

Two, they have a corporate farming scheme for more crops while our corporate farming is limited mainly to bananas and pineapple.

Three, they have a low tax on diesel (used by agricultural machinery like tractors, harvesters, trucks, irrigation pumps, etc.), with their import tax for gasoline reduced from 10% to 5.62% in July 2023, and diesel taxed by only 0.58%. Meanwhile, the Philippines raised the diesel excise tax from zero in 2017 to P6/liter by 2020 under the TRAIN law.

And, four, they have good trade relations with China and are able to have more agricultural exports to China. They are not warmongering, unlike the current saber-rattling in the Philippines against China over the West Philippine Sea.

Plus, Vietnam has good geography. It has a contiguous mainland and a good, extensive irrigation system thanks to the Mekong River and Tonle Sap.

The economic team may work with other departments to address the above issues. Like working with the Department of Agrarian Reform on how to end agribusiness’ uncertainty over the endless land redistribution schemes, working with the Department of Trade and Industry on corporate farming, and with the Departments of National Defense and Foreign Affairs on diplomacy and trade with China.

Finally, President Marcos Jr. and Finance Secretary Ralph G. Recto should consider reversing the policy of “expensive diesel to save the planet” engineered by former Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez. As I have argued in this column since 2015, I never supported that policy. We should focus on saving our farmers and the hungry partly via cheap diesel; not “saving the planet” via a high diesel tax.

Sure, there will be revenue declines if this is done, but this can be compensated for via spending cuts somewhere, plus revenues from the privatization of some big government assets and land. Higher food production and lower food inflation are goals of higher importance than saving the planet and saving certain bureaucracies and freebies.