* This is my article in BusinessWorld last November 21, 2017.

See also:

BWorld 91, Free trade means faster growth in manufacturing, November 14, 2016

BWorld 137, ASEAN trade expansion and RCEP, June 20, 2017

BWorld 164, PES conference amidst reduced risk and uncertainty, November 21, 2017

During the ASEAN Summit + Related Summits in Manila,

trade and the further deepening of economic integration was among the major

topics. There were new initiatives as well as updates to existing negotiations

at multilateral and bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs).

Here are some of those old and new FTAs as reported in

BusinessWorld from Nov. 13-16:

1. “ASEAN, HK sign free trade, investment deals” — the

ASEAN-Hong Kong FTA (AHKFTA) and ASEAN-Hong Kong Investment Agreement (AHKIA).

2. “Do you know your TPPs from your RCEPs, NAFTAs and

OBORs?” — about the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Trans-Pacific

Partnership (TPP), Regional Economic Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP), One Belt

One Road initiative (OBOR), North America FTA (NAFTA).

3. “ASEAN claims ‘significant progress’ on RCEP” —

mentioned the ASEAN Seamless Trade Facilitation Indicators (ASTFI), ASEAN

Inclusive Business Framework (AIBF), others.

4. “US agrees to explore FTA with Philippines” — to be

called the US-Philippines Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA).

Free trade is good, regardless of what those against it

would say because it always results in “net gains.”

There are always gains/winners and pains/losers the same

way that there are gains and pains under protectionism. When people withdraw

their savings for several months in exchange for a new car or dream vacation,

they derive net gains from trade of savings vs. vacation.

ASEAN is known for its fast pace of tariff liberalization

towards zero compared to many other economic blocs in the world. That’s the

good news.

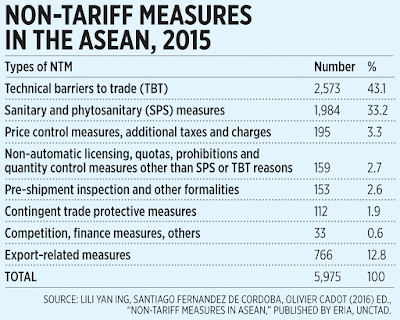

The bad news is the big increase in non-tariff barriers

(NTBs) or non-tariff measures (NTMs). These are restrictions and barriers other

than tariffs and taxes that make imports or exports of products more difficult,

more complicated and hence, more costly (see table).

The authors also noted that “As the average tariff rates

of ASEAN countries decreased from 8.9% in 2000 to 4.5% in 2015, the number of

NTMs had increased from 1,634 measures to 5,975 measures over the same period.

The increase of NTMs was notable not only in ASEAN but also around the world,

particularly, between 2008 and 2011.”

Among ASEAN member-states, Thailand has the highest

number of NTMs at 1,630, 2nd was the Philippines with 854, 3rd was Malaysia

with 713, 4th was Indonesia with 638, 5th was Singapore with 529, 6th Brunei

with 516, 7th Vietnam with 379, 8th Laos with 301, 9th Cambodia with 243, and

10th was Myanmar with only 172.

The most common NTMs in Thailand and Myanmar was sanitary

and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures while for the other eight ASEAN countries,

technical barriers to trade (TBT) was most common.

So which way to achieve regional if not global free

trade: (a) Multilateral via World Trade Organization (WTO), APEC, TPP, RCEP,

AEC, others ; or (b) bilateral like US-Philippines TIFA, Japan-Philippines

Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA)?

The advantage of multilateral liberalization is that all

economies in the world or at least in the region are committed to bring down

their tariffs and NTMs. The disadvantage is that under WTO, real liberalization

remains far off even after 22 years (1995 to present) of numerous negotiations.

The setback of regional FTAs is that while

member-countries can have near-zero tariff and reduced NTMs, other countries

outside the FTA are slapped with high tariffs and/or multiple NTMs.

The advantage of bilateral liberalization is that

differences and disputes can be ironed out easier and faster so that FTA can

materialize soon. The disadvantage is that a country will need to dispatch

plenty of trade negotiation teams to deal with many countries and hence, it can

be costly and messy.

A third way is via unilateral liberalization.

Just bring down the tariffs and NTMs, open up the borders

with little or no conditions. The main advantage of this move is that it can be

done quickly with very little trade negotiation teams and hence, non-costly to

taxpayers. However, the disadvantage is that it is “too scary, too radical” for

many people as it might result in massive labor displacements.

There are a few countries that boldly took unilateral

liberalization and so far, almost all of them have attained economic prosperity

in just a few decades such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai/UAE, Chile.

Unilateral liberalization in goods has been done by the

ASEAN as a bloc. The challenge is unilateral liberalization in services.

With continued modernization in the information and

communications technology worldwide, it is much easier, not harder, to

liberalize trade in services.

Asian economies, the Philippines in particular, should

consider a unilateral liberalization policy. This would involve fewer trade

bureaucracies, taxes and subsidies, and more competition from more suppliers

and manufacturers from countries around the world. Local consumers will benefit

from more choices and more options while shelling out less taxes and fees.

Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. is President of Minimal

Government Thinkers, a member-institute of Economic Freedom Network (EFN) Asia.

---------------See also:

BWorld 91, Free trade means faster growth in manufacturing, November 14, 2016

BWorld 137, ASEAN trade expansion and RCEP, June 20, 2017

BWorld 164, PES conference amidst reduced risk and uncertainty, November 21, 2017

BWorld 165, Airport transfers and tourism, November 25, 2017

BWorld 166, US energy trading and implications for Asia and Philippines, November 26, 2017

BWorld 166, US energy trading and implications for Asia and Philippines, November 26, 2017