http://www.interaksyon.com/business/41795/fat-free-economics-three-years-of-drug-price-control-policy

---------

The drug price control policy turned three years old in mid-August. The Maximum Retail Price or MRP was imposed through Executive Order No. 821 and Advisory Council Resolution 2009-001 - both issued in July 2009 and took effect August 16, 2009.

The imposition was driven by a political emergency and not a health emergency, as the Presidential and local elections were just nine months away back then.

Prevailing drug prices data at that time contradicted the necessity of imposing price regulation. Competition among various brands from different drug manufacturers and drugstores was healthy at that time, such that consumers had various options for their needs.

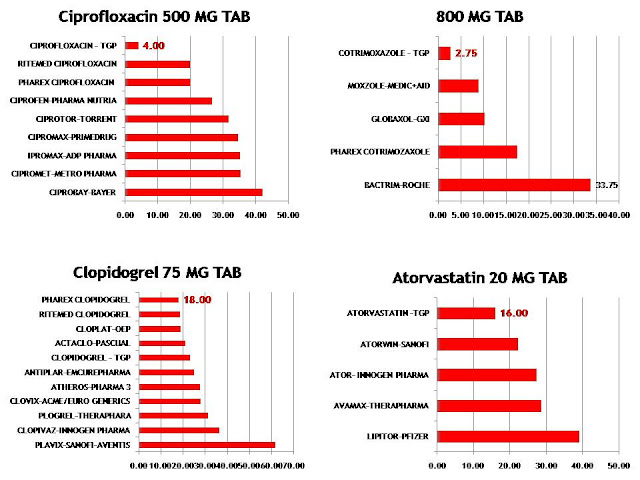

Three examples of drugs are given below. Data came from Tomas Marcelo “Beau” Agana, who is president of the Philippine Chamber of Pharmaceutical Industry. Beau prepared a PowerPoint for the public hearing of the Congressional Oversight Committee on Republic Act No. 9502 last May at the Senate. But due to limited time, Beau was unable to present it. The event became a “public speaking” -instead of a public hearing - by Rep. Ferjenel Biron and Sen. Manny Villar, as both were pushing their respective bills creating a new bureaucratic layer, the Drug Price Regulation Board.

First is amlodipine, an anti-hypertension drug. While the leading brand, Norvasc by Pfizer, was selling for around P38 for the 5 milligram tablet, similar drugs were selling for P25, P15, P11 and P10. Consumers had choices, but the politics of envy centered on Norvasc. So their solution was more politics, more government coercion.

Source: Agana, May 2012. Primary data for the second chart - prices of different brands - is from the Drugstore Survey, March 2012.

Beau showed that for the average retail price for various brands of amlodipine, Philippine prices were cheaper than those in Indonesia, but more expensive than those in Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand.

Now consider this: some countries - such as Malaysia - do not slap taxes on medicines. Philippine taxes on medicines include an import tax of 3-5 percent and value-added tax of 12 percent - all of which result in a 15 percent price spike. If other taxes and fees are included - local taxes and fees and Food and Drug Authority fees - the government share could rise up to 20 percent of the retail price.

Then there are indirect taxes on medicines, namely the corporate income tax and the mandatory social security contributions by drug manufacturers, wholesalers and importers, and drugstores. Those taxes and fees, direct and indirect, are passed on to consumers.

Thus, the price difference of amlodipine between the Philippines and Malaysia could pretty much approximate the difference in tax treatment they both applied (or not applied) on medicines and on corporations: 12 percent VAT in the Philippines vs. zero in Malaysia; and 32 percent CIT in the Philippines vs. 20 percent for the first RM 500,000 and 28 percent on the balance.

Second case is co-amoxiclav, an anti-infection drug. Before the MRP policy three years ago, the leading brand, Augmentin by GSK was selling for nearly P83 for the 625 milligram bottle. But consumers had other options that were selling for only P59, P47, or P35.

Comparing again with some Asian countries, drug prices here for co-amoxiclav were similar with those in Indonesia and Thailand. The price difference with Malaysia because of a different tax treatment appears to explain why they are cheaper in Malaysia.

Comparing with prices in Singapore, VAT in the city-state stands at only 5 percent and CIT at 17 percent, or almost half that in the Philippines.

The third case is simvastatin, a drug against high cholesterol and certain cardiovascular diseases. See the different prices for different brands.

And here are other drugs and their respective price ranges. Again, basic data is from the Drugstore Survey, March 2012.

The bottomline for all these data is clear: there is competition, there are various options for the consumers, and therefore government intervention in drug price setting was unnecessary and unjustified. Only then Senator Mar Roxas (who pushed for the policy in the Senate) and then President Gloria Arroyo knew why the MRP was imposed.

When the MRP was being cooked and debated, Roxas was desperate to raise his low approval rating for the May 2010 Presidential elections, while Arroyo signed the EO to steal the show from him. Then Health Secretary Francisco Duque was also looking at the possibility of running for the Senate, but did not push through with the plan because of the Arroyo administration's poor showing in surveys.

In short, the MRP imposition in August 2009 was a political gimmick for political ends by politicians looking at the elections just nine months away. While their political horizon was short term, the social and economic damage was long term. EO 821 has no sunset provision.

A year after the MRP was imposed, the key sponsors of the policy had dropped the drug sector like a hot potato: Arroyo won a congressional seat, Roxas was appointed transport and communications secretary, and Duque was appointed head of the Civil Service Commission.

Two weeks ago, I attended the emergency meeting of the DOH Advisory Council for RA 9502, the Cheaper Medicines Law, and the important question requiring an answer was: What should the DOH do, to deal with repeated if not rising cases of water-borne diseases like leptospirosis due to flooding? Should the government impose another round of MRP on drugs used to treat those diseases?

Luckily the lesson of the past three years of MRP is clear in the minds of the Advisory Council members. Competition among different brands and drugstores provides the poor some access to cheap drugs, whereas price control has upset the market for the same.

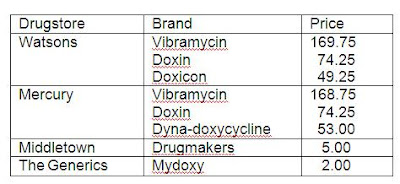

Below is data presented during the said meeting. The drug against leptospirosis, doxycycline, has various brands with a wide price range. The prices are in pesos per 100 milligram capsule.

So consumers have the option of buying at P169, P74, P49, P5 or P2. Furthermore, many drugs against diseases that arise during calamities are given away not only at low prices, but sometimes for free through donations from various civil society and charitable organizations like the Red Cross, Rotary, Mason, Lions, JCI, etc. The DOH also has its own stock of medicines for distribution to the poor.

Competition, not more government coercion. Deregulation, not more government regulation and taxation. The public and the politicians would be better off if they will heed this simple lesson from the three years of drug price control.

--------

See also:

Drug Price Control 25: Top 10 Articles on Google Search, April 03, 2012

Drug Price Control 26: Conflict of Interest in Drug Price Regulation Legislation, May 13, 2012

Drug Price Control 27: Letter to Sen. Pia Cayetano, May 15, 2012

Drug Price Control 28: On Cong. Biron and Sen. Villar Bills, July 14, 2012

Drug Price Control 29: MRP Attempt Over Anti-Leptospirosis Drug, August 16, 2012

Fat-Free Econ 8: Drug Price Regulation is Wrong, May 04, 2012

Fat-Free Econ 9: Drug Pricing Bureaucracy is Not Cool, May 11, 2012

Fat-Free Econ 18: Healthcare Corruption and Physician Entanglement, July 30, 2012

1 comment:

I dont know what your point is: does MRP hurt anyone? how?

Post a Comment